KATHE KOLLWITZ is one of the most well known German and European women artists of the 20th century. She turned the piercing and tragic truths of her life into her Art. Her loss and grief from both World Wars did not discriminate between “sides.” She recognized that her son (Peter), and later her grandson (also Peter), were claimed by the same historical machine—the machine of European imperial power, militarism, and the idea that the young male body is expendable fuel for national myth.

The Continuity of Militarism

Kollwitz saw WWI and WWII not as different wars, but as one unbroken historical catastrophe. WWI was framed as national honor and the defense of civilization and WWII was framed as racial destiny and imperial expansion. Yet beneath the speeches, flags, and uniforms—the same sacrifice of sons.

She understood this intimately, painfully. She lost her son Peter in 1914. He volunteered in a wave of patriotic fervor—what she later saw as collective hypnosis.

Her grandson Peter died in 1942. He was drafted into Hitler’s war of conquest—what she recognized as ideological captivity. In both cases, the state claimed the bodies of the young. And in both cases, the mothers were left with the grief.

In Kollwitz’s own words, she states, “I see the lives of my son and my grandson as strands in the same net of war, thrown over the youth of Europe.”

• She saw that militarism is not episodic, it is structural.

• War is not an accident; it is a method of maintaining power.

• The young, especially young men, become the raw material of empire.

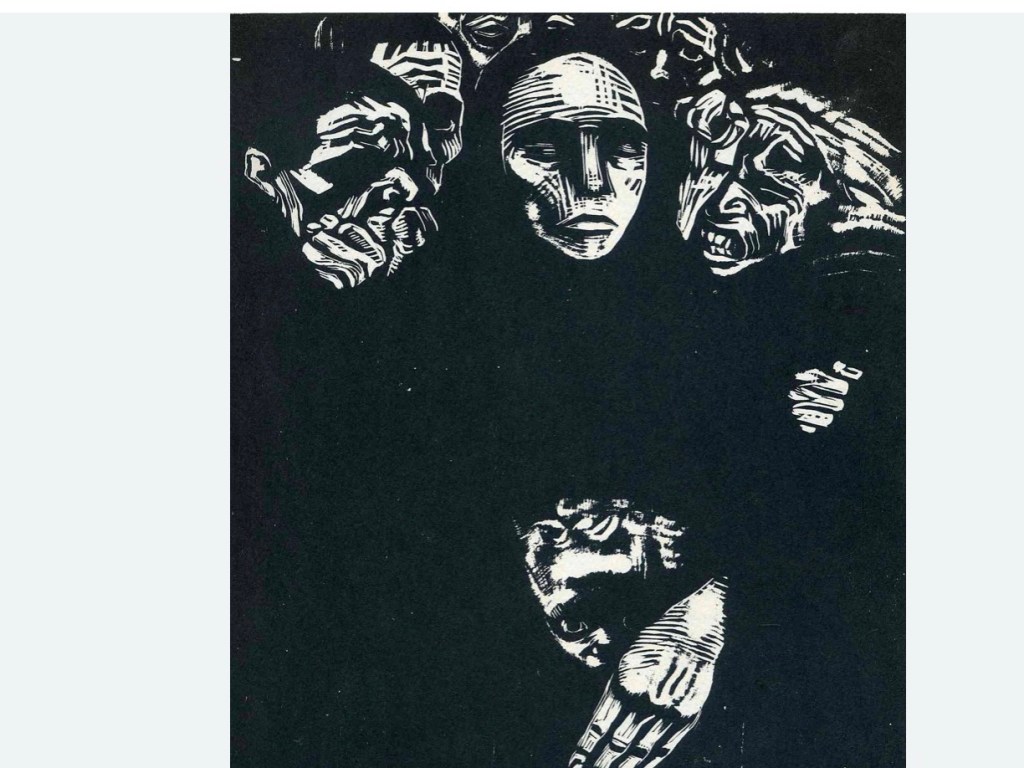

This viewpoint explains how Kollwitz’s art is never nationalistic, never triumphant, never sentimental.

Her mourning is not just personal—she is against the militaristic, and Patriarchal systematic hierarchy. She sees mourning for the lost sons and grandsons as episodic.

The European-Centric Ideology

The ideology that produced these wars was fundamentally:

• Eurocentric

• Colonial

• Capital-driven

• Patriarchal

Both wars can be understood by competition, domination and revenge. Men paid the highest cost of these wars. The European military complex valued young men for their “heroic male sacrifice.”

These wars were not “defending civilization”—they were attempts to extend it as domination. And in both wars, the rhetoric of “duty” and “manhood” was used to send sons to die.

Kollwitz’s entire body of late work is a counter to this myth. Where the state says: “Your son died for the Fatherland and is immortal.” Kollwitz answers: “No. Your son dies. And the mother is left with an empty room.”

Her images silence the propaganda because grief is the truth that empire cannot aestheticize.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was dismissed from her teaching position at the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1933, shortly after the Nazis took power. She was also forced to resign from the Academy’s Senate and forbidden to exhibit publicly. After this dismissal, her life during the years leading up to and including WWII was marked by isolation, mourning, and quiet resistance, but also continued artistic production—especially drawing and lithography.

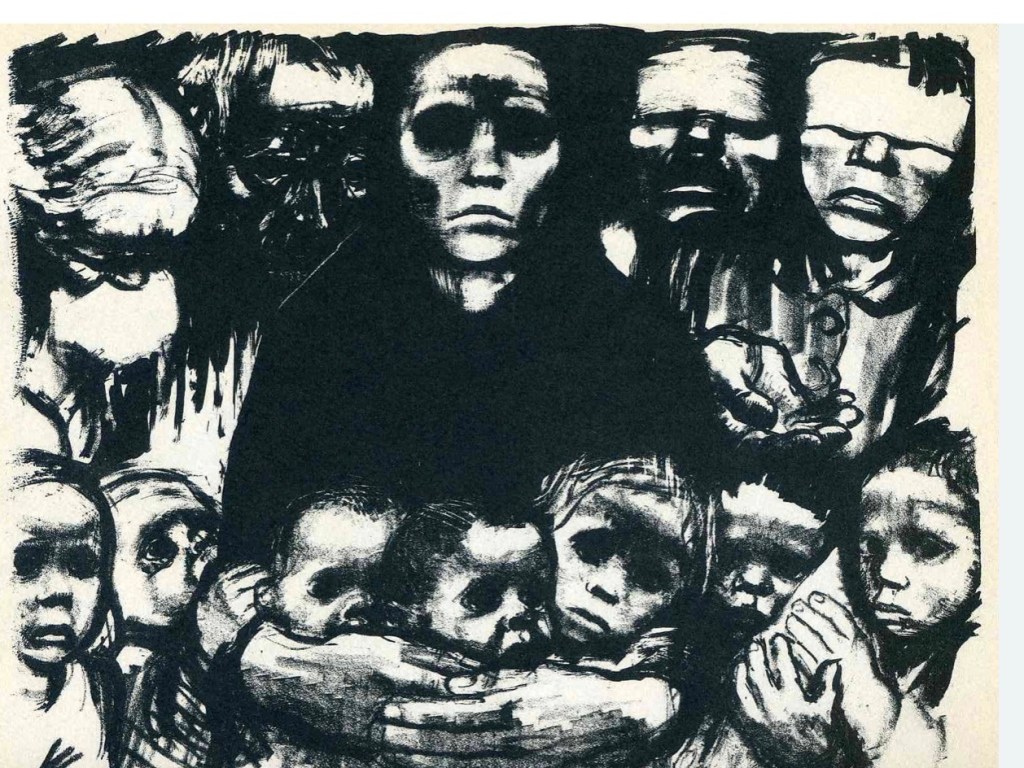

During WWII she continued to Produce Drawings and Lithographs. Although she was banned from showing her work, Kollwitz continued to draw. She shifted toward more introspective, spare, and universal images of sorrow, often mothers and children held in tightly composed forms. Her style became more distilled—an art stripped to grief and compassion.

Her subject matter continued to center on human suffering, especially mothers mourning sons—reflecting both her personal losses and the destruction of Berlin, her hometown during WWII.

The Nazi regime monitored her but did not arrest her—partly because of her international reputation and the potential backlash. She avoided overt political statements but did not cooperate with Nazi cultural institutions.

Her husband Karl (until his death in 1940) was a Doctor and they helped those who were displaced or impoverished. Their home became a place of discreet support for individuals suffering under the regime—particularly workers and widows.

Grieved Personal Loss During the War

Her grandson, Peter (named after her son who was killed in WWI), was killed in WWII in 1942. This loss profoundly deepened her sense of shared grief with mothers across generations and wars—this becomes visible in her later drawings .

In 1943 she moved to Nordhausen, outside of Berlin. And then in 1944, she moved to Moritzburg, near Dresden, where she spent her final months. She died in April 1945, just weeks before the end of the war.

Significance of her work

Kollwitz’s stance during WWII is often described as a moral resistance, not militant resistance. Her work is a sustained lamentation—that refuses to glorify war, nationalism, or sacrifice. Her images became, and remain, among the most powerful visual articulations of anti-war aesthetic consciousness in the 20th century.

Her late art embodies what Adorno might call “suffering that speaks”—grief not sublimated into ideology, but left raw and seen.

Key References

Hinz, M. (1997). Käthe Kollwitz: Life and work. Abrams.

Prelinger, E. (1992). Käthe Kollwitz. National Gallery of Art.

Kollwitz, K. (1988). The Diary and Letters of Käthe Kollwitz (R. Taylor, Ed.). Northwestern University Press.

Zuromskis, C. (2010). The human image in German anti-war art. Modernism/modernity, 17(3), 524–544.