In Aesthetic Theory, Adorno (1970/1997) describes spirit (Geist) as the principle that “works the material” of art, and as the rational consciousness that draws order from chaos and prevents aesthetic creation from collapsing into myth. For Adorno, art embodies a tension between mimesis—the expressive, nature-bound impulse—and spirit, the shaping intellect that mediates and transforms (pp. 117–120). Yet even as his philosophy critiques Enlightenment reason, this framework privileges a hierarchy: spirit is supreme, as it is the architect of form, the cosmos-maker that wrests coherence from matter. Creation still implies mastery—the triumph of reflection over immediacy—although Adorno also argues that art’s truth-content emerges in the unresolved tension of the artwork (pp. 114–120), so not everything is resolved in this hierarchy.

Adorno further emphasizes that this formative principle arises through the dialectical interplay of forces: the resistance of material, the generative impulse of spirit, and the historical and social conditions of production. This principle is universal in structure, (it affects all artists, all workers, all creators) but it is always realized in concrete, particular forms: a specific painting, sculpture, or musical composition. It is in this interplay that the artwork gains its singularity and particular truth-content (Wahrheitsgehalt), defying full rational comprehension or conceptual identity (Adorno, 1970/1997, pp. 114–120). Each artwork embodies the universal without becoming a formula, carrying the historical sediment of its creation and the unique tension between form, material, and emergent spirit.

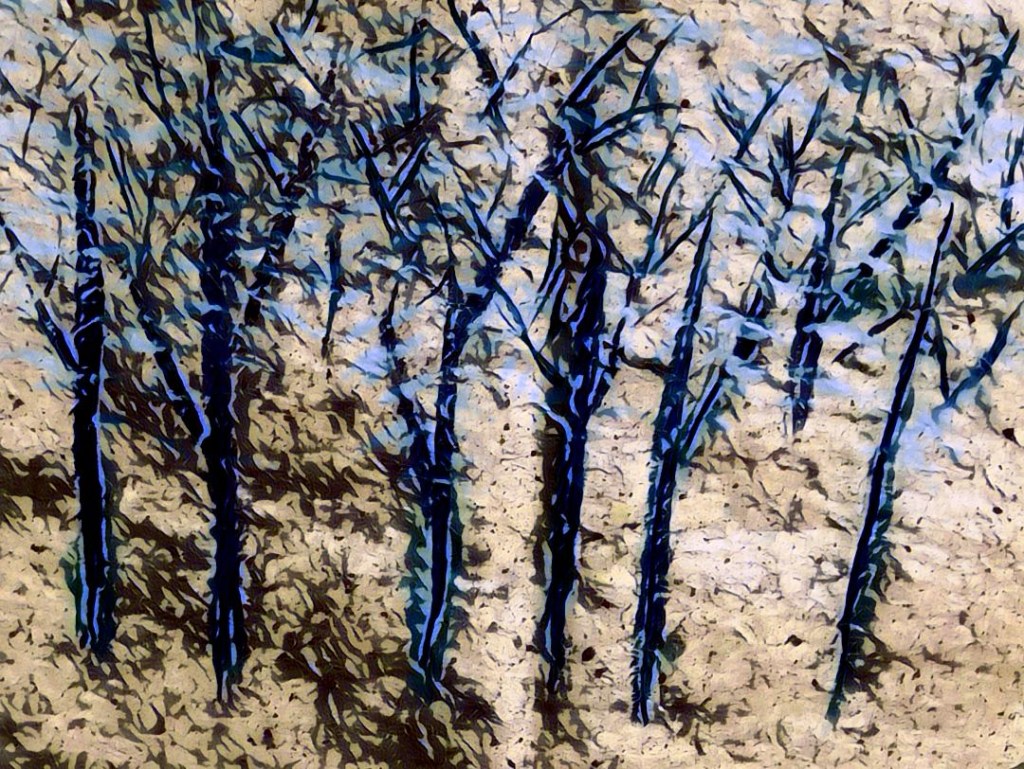

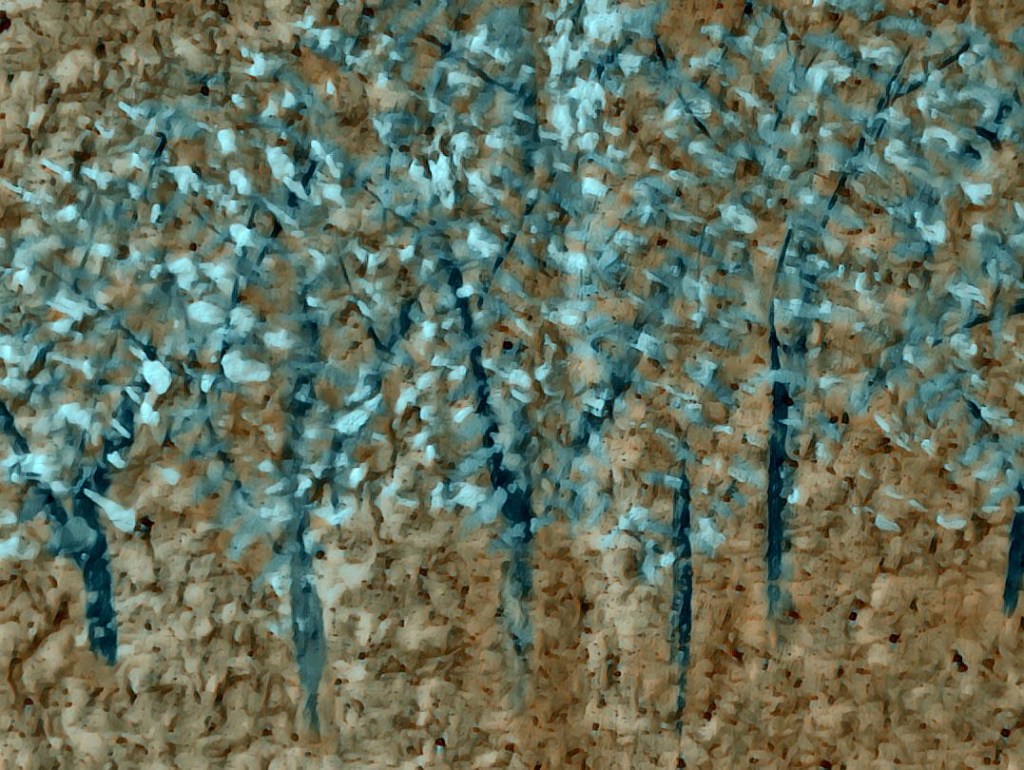

Ch’an philosophy offers a cosmology that dissolves hierarchical mediation. In Chinese Taoist thought, Qi is both life force and matter, both consciousness and the energy of form itself. As Hinton (2019) explains, “The Cosmos is a single tissue of generative energy—Qi—moving as a self-generating process of transformation” (p. 13). Creation is not imposed by intellect but arises through attunement, as the artist participates in the living field of generative transformation. My own process echoes this orientation: painting becomes listening rather than directing, a meditative responsiveness where gesture, texture, and color unfold of themselves. What Adorno (1970/1997) calls the enigmaticalness of art—the intertwining of rationality and mimesis—becomes, in the Ch’an sense, the direct manifestation of Qi: energy, matter, and spirit breathing as one.

The Jewish mystical concept of the Shekinah parallels Qi as an immanent, generative, and feminine principle. In Kabbalistic thought, the Shekinah is the indwelling presence of God, associated with light, breath, the life-force, animating the world from within. Like Qi, it is co-creative rather than dominating: it emerges in relation, flowing through matter and consciousness alike. While Adorno might classify mythic narratives as externalizing or explanatory (Adorno, 1970/1997, pp. 105–110), the Shekinah, when understood phenomenologically, functions as a symbol of immanent formative energy, analogous to the enigmatical spirit in art.

Integrating these frameworks offers a feminist and ecological re-vision: the artist does not impose order from above, but participates in a relational field of generative energy. Breath, energy, light, and material co-arise, revealing a cosmos that is neither wholly rational nor wholly natural, neither fully abstract nor fully determinate. Art, then, becomes the expression of universal principles realized in historical and material particulars, resisting identity, formula, or total comprehension. It is in this singular, enigmatic manifestation—whether understood as Adorno’s spirit, Ch’an Qi, or the Shekinah—that creation reveals its deepest truths.

References

Adorno, T. W. (1997). Aesthetic theory (R. Hullot-Kentor, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1970)

Hinton, D. (2019). China root: Taoism, Ch’an, and original Zen. Shambhala Publications.

Hinton, D. (2016). The wilds of poetry: Adventures in mind and landscape. Shambhala Publications.

New Works in progress